Blog

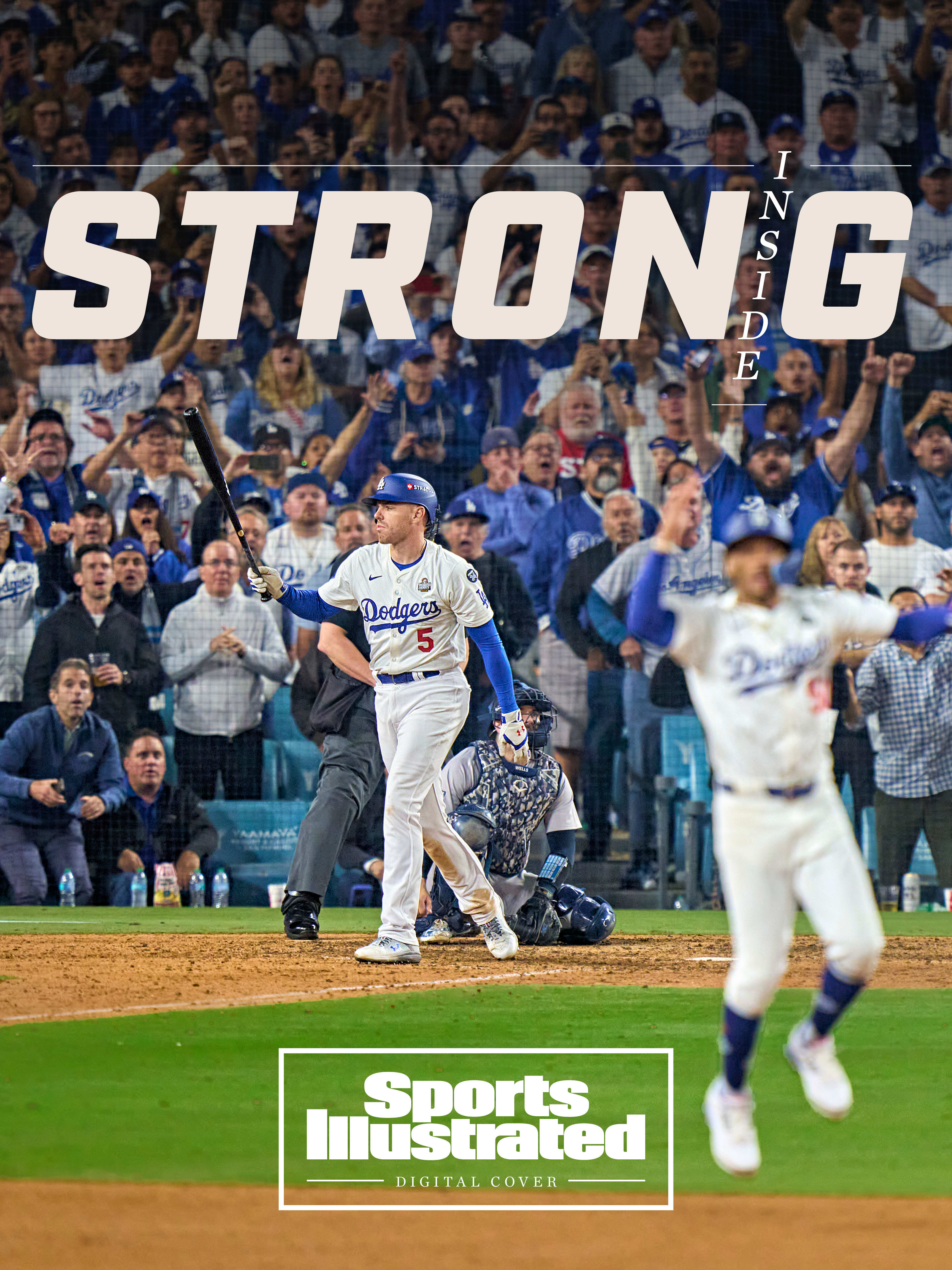

Freddie Freeman Defined Strength for the Title-Winning Dodgers

As he coped with his son’s illness and his own injuries, the Dodgers first baseman displayed resilience (and a knack for looking for the right pitch) in a historic World Series performance.

As we count down the final days of the year, SI writers are reflecting on “The Best Thing I Saw in 2024” and looking back at the most memorable moments they witnessed in their reporting this year.

WHAT DOES it mean to be strong? Physical power, of course. Strong is rooted in Old English and Germanic words for severe and taut, as in a cord. Strong, as in what it takes to blast one of the greatest World Series home runs ever hit.

Strong also means power beyond the physical. It is the tautness of will. It is enduring a broken right middle finger, a bone bruise and severe sprain of the right ankle and a broken costal cartilage of the sixth rib and getting shot up with a numbing agent in between at bats of a playoff game—all within 50 days.

It is rushing 1,300 miles home to find your child fighting for his life, hooked up to feeding tubes and a ventilator while his body is in full paralysis.

“To physically see your 3-year-old son not be able to breathe on his own, it was … ” says Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman Freddie Freeman, as his voice cracks at the memory of his son Maximus in July. “I mean, you can still hear it in my voice. It’s hard. Really hard. No one should ever go through that. And it’s just … It was just sad.”

This was the year Shohei Ohtani and Aaron Judge rewrote history. Ohtani became the first player with 50 home runs and 50 stolen bases in a season. Judge joined Babe Ruth as the only players not connected to PEDs to hit 50 homers a third time. But if you want the best proxy for baseball in 2024—not because of one famous swing but because of the strength behind it—then this is the Year of Freddie.

“You know, I’ve been through a lot in my life,” Freeman says. “I lost my mom [to skin cancer] when I was 10 and I almost lost my dad to a heart attack when I was 12. I think things happen in life for a reason.

“I’ve never been patient about my swing or something that I expect to happen. I want to be good that minute. With this, you couldn’t have anything happen that minute. You had to wait. You had to wait to see if it was going to work out.

“You had to wait for him to recover. You had to wait for him to eat ice again so he can come out of the hospital. I had patience. I think that’s what I learned.”

Ernest Hemingway wrote A Farewell to Arms by drawing on his service as a volunteer ambulance driver in World War I, when shrapnel from a mortar blast on the Italian front mangled his leg. “The world breaks everyone,” he wrote, “and afterward many are strong at the broken places.”

THE SIXTH batter due in the bottom of the ninth inning of World Series Game 1, Freeman did not see history on his doorstep. He was nothing more than a cheerleader then, rooting for the bottom of the lineup to mount something against the Yankees’ 3–2 lead. Then fortune fell L.A.’s way as crazily as lucky Pachinko balls. A walk, a single off the second baseman’s glove, a pitching change in which New York asked Nestor Cortes, a left-handed starter, to save a game for the first time in his seven-year major league career … every ricochet meant history was drawing nearer to him.